Body Art?

Is Body Worlds 2 an Art Exhibition?

Gareth Bate

Jan 25, 2006. Revised Feb. 2011

Photo copyright James Wray, London.

All artists, on some level, hope their creations will endure far beyond their limited life spans. They are grasping for eternal life, a legacy. The dead people featured in The Ontario Science Centre's Body Worlds 2: The Anatomical Exhibition of Real Human Bodies, have chosen to make their bodies their living legacy. Although billed as a scientific exhibition, the artistic sensibility of the show's creator and all the ethical questions that it implies, are very much present in the show.

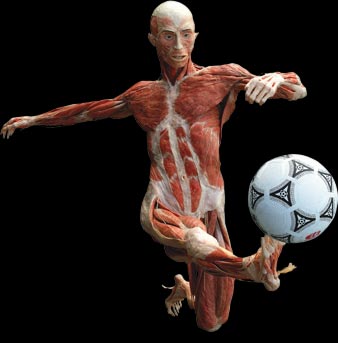

This comprehensive introduction to the human body, famous for its full body "plastinates" has already been seen by 17 million people world wide. It made its Canadian debut from Sept. 30, 2005 to Feb. 26, 2006. The bodies are posed in elaborate sporting positions like that of a soccer player, ice skaters, javelin thrower, skate boarder, ballet dancer etc. The plastination process, which takes over 1500 hours, was invented by German anatomist Dr. Gunther von Hagens in 1977. Normal bodily fluids are extracted and replaced with plastic resins pumped through the body in a "forced vacuum impregnation." This method perfectly preserves every detail of the body to create a hard, odourless and dry specimen.

There is something remarkably beautiful about athletically posed specimens like The Soccer Player or the piece called Elegance on Ice featuring male-female pairs ice skaters, or the stunning head composed entirely of red blood vessels which creates an exact structural likeness. They are all marvels of complexity and intricacy. Although none of the bodies are posed in the style of Hellenistic Greek sculpture, the influence is unmistakable. The frozen movement of flexing and twisting stomach muscles and the jutting legs of the soccer player evoke the linear beauty of The Discus Thrower. It is, dare I say it- sexy. Superficial Muscle Man evokes Michelangelo's David while one relaxed and contemplative pose evokes Rodin's The Thinker. I am also reminded of the total celebration of the ideal human body in Olympia by Nazi filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl. I think she would have loved Body Worlds. Though von Hagens adamantly denies that his plastinates are works of art, at the same time, he acknowledges the importance of aesthetic poses as pleasing ways to connect the viewer with specimens that, in their vividness, are not always easy to relate to.

I did feel a sense of unease at wondering who these people were and how they died, especially in the case of the pregnant woman, a work titled rather insensitively Woman Bearing Life. She was presented in a dark room that you had to enter by your own will. There she lay stretched out like an Ingres odalisque. It is desturbing to think that this woman donated her body without knowing that she would die while at least eight or nine months pregnant.

A few other dissections are disturbing because of their almost horror movie aesthetic or because of the flamboyant, even outrageous "artistic licence" von Hagens employs in a piece like Drawer Man where the body's special feature is a series of drawers which, when pulled out, reveal the subject's insides. Another piece bordering on going too far is The Exploded Man, in which all the body's muscles and internal organs have been separated and suspended with strings to allow all sides to be viewed simultaneously. Even the striking Elegance on Ice sculpture, for some reason included some pubic hair on the skinless woman. As I was drawing this piece in my sketch book, I observed that literally no one failed to notice this.

One of the most disturbing bodies was the morbidly obese man cut into multiple parts to reveal just how much of his body mass was in fact fat. Some of the slivers were literally nothing but fat with no organs or skeletal structure at all. That image was memorable to say the least and really drove home the importance of caring for one's body. This man stands in stark contrast to the other specimens who are there to represent the pinnacle of health. I think we can safely assume they didn't all live that way in real life.

Also disturbing is Drawer Man's white pigmentless skin which is reminiscent of the full body cast sculptures of artists like George Segal and Anthony Gormley. The skin is the flaw of Body Worlds as it is currently not possible to make it look life like. One could imagine that if it were possible to preserve the skin in an attractive way, that plastination would become the mummification of the 21st century. People would start having themselves preserved as sculptures.

One cannot help but ponder questions of mortality at this exhibition. I found myself constantly looking back and forth between the plastinates and their living counterparts visiting the show. I was struck by how completely unalike they were despite their displaying the same form. The media is constantly bombarding us with images of beautiful healthy bodies and this show certainly demonstrates that physical beauty is not only on the outside. However, though there is something noble, dignified and even beautiful about what has become of these bodies, they are very dead indeed. I am very grateful to the body donors as well as von Hagens for helping me see the amazing aesthetic of the internal human body.

© Gareth Bate, 2011